"[...] Apponyi then, claiming that he could not hear well, took his chair and sat down at Lloyd George's desk and laid before him an ethnographic map based on the 1910 census data [...]"

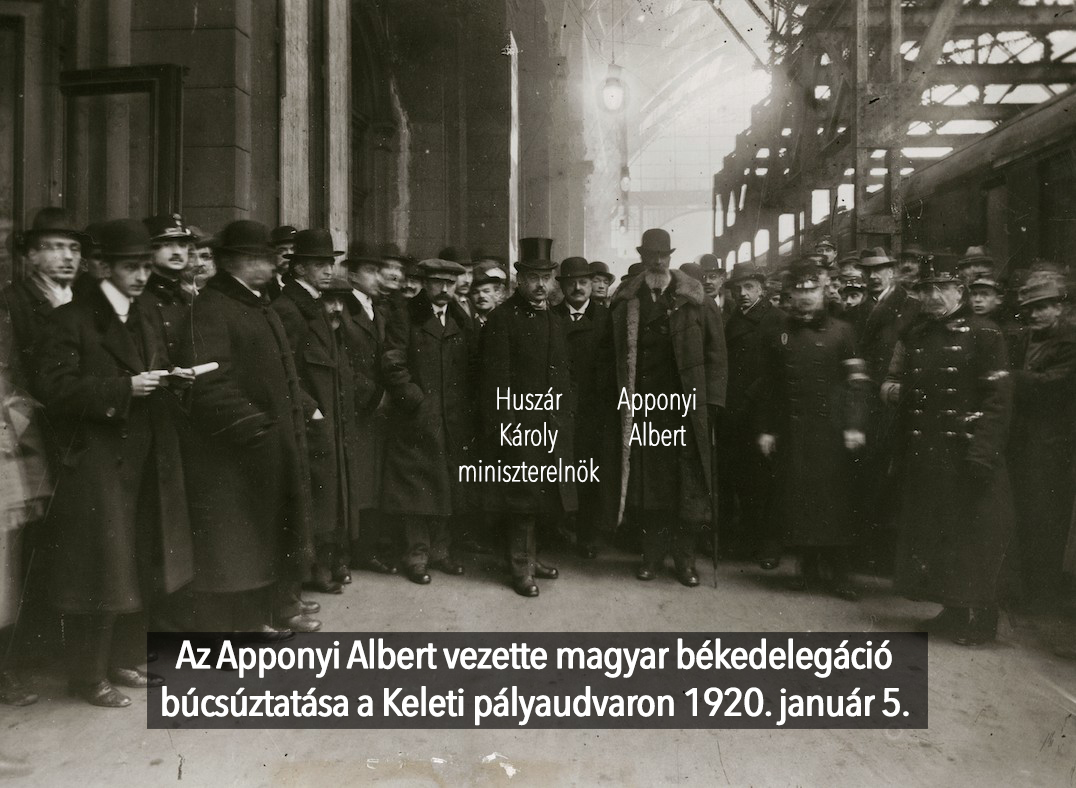

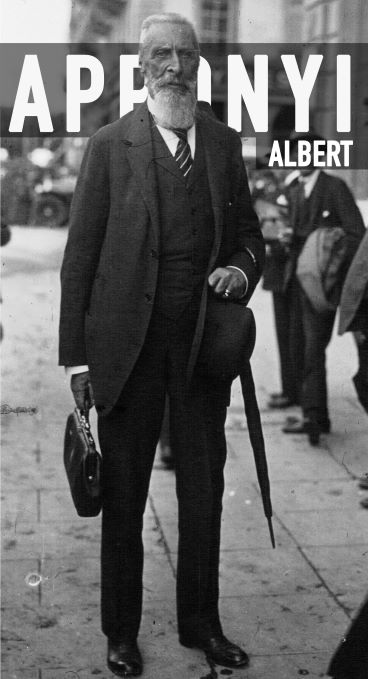

"The day of Apponyi's great exposé..." - 103 years ago, on 16 January 1920, on this day, Count Albert Apponyi delivered his famous defence speech, article by Tamás László Vizi, Deputy Director General for Science. The train carrying the Hungarian peace delegation, led by Count Albert Apponyi, rolled out of Budapest's Eastern Railway Station shortly before 9 a.m. on 5 January 1920, and arrived at Paris's Eastern Railway Station, Gare de l'Est, two days later, at 8.15 a.m. on 7 January.

On 16 January 1920, Apponyi had the opportunity to verbally reflect on the draft peace treaty submitted by Clemenceau to the Hungarian delegation on 15 January 1920. His speech took place at 3 p.m. in the building of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in the room of the French Foreign Minister, Stephen Pichon, where the High Council used to hold its meetings. Representatives of the five main powers were present on behalf of the winners: Georges Clemenceau (Prime Minister of France), David Lloyd George (Prime Minister of Great Britain), Francesco Saverio Nitti (Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Italy), Henry A. Wallace (US Ambassador in Paris) and Keishirō Matsui (Ambassador of Japan in Paris), as well as George N. Curzon, Foreign Minister of Great Britain.[1]

At the beginning of the meeting, without any introduction, Clemenceau invited the head of the Hungarian delegation to deliver his presentation, and offered him to do so while seated. Apponyi politely declined, saying, "Allow me to stand, because I am used to it and I prefer it." Apponyi began his speech by stating that the peace terms were "unacceptable to Hungary without substantial modifications." He then continued, "We cannot conceal, above all, our shock at the immense severity of the peace terms." Especially because, if they were fulfilled, Hungary would lose two-thirds of its territory and almost two-thirds of its population. Moreover, these peace terms were drawn up by the victors without even consulting the Hungarian side or its representatives.

After the above introduction, Apponyi turned to the first element of his argument, the ethno-national arguments. He pointed out that 35% (3.5 million) of the 11 million people to be separated from Hungary are Hungarians. Due to the large number of Hungarian minorities thus created,

THE SUCCESSOR STATES WILL BE 'BROKEN INTO EVEN MORE PIECES THAN THE OLD HUNGARY' FROM AN ETHNIC/NATIONAL POINT OF VIEW.

In this context, Apponyi emphasised that the nationality principles advocated by the Entente were not, and could not be, realised in the case of the new states.

In this part of his speech, Apponyi raised a new, previously unmentioned element of the Hungarian arguments, namely the theory of cultural supremacy. He argued that the Hungarians were on a much higher cultural level than the majority nations of the successor states (Slovaks, Romanians, Serbs). He tried to substantiate this claim with concrete numbers, and presented two figures to support his claim:

WHILE AMONG HUNGARIANS THE LITERACY RATE WAS CLOSE TO 80%, IT WAS 33% AMONG ROMANIANS AND 59% AMONG SERBS. IN THE UPPER SOCIAL CLASSES, 84% OF HUNGARIANS HAD A HIGH SCHOOL DIPLOMA, WHILE AMONG ROMANIANS THIS PERCENTEGE WAS ONLY 4%.

However, this argument of his could have backfired, as these data could have served as a basis for reflecting the oppression of ethnic minorities by Hungarians.

ACCORDING TO APPONYI'S VIEW, IF THE HUNGARIANS WITH A HIGHER CULTURAL LEVEL IN THE SUCCESSOR STATES FALL UNDER THE RULE OF NATIONS WITH A LOWER CULTURAL LEVEL, THE WHOLE OF UNIVERSAL HUMAN CULTURE WILL BE ADVERSELY AFFECTED.

At this point, the Count cited two examples that could be seen as a serious argument in every respect: he described the sad fate of the universities of Kolozsvár (today: Cluj-Napoca, RO) and Pozsony (today: Bratislava, SLO), where dozens of Hungarian professors were expelled by the authorities of the successor states.

Apponyi continued his speech by discussing the right of peoples to self-determination. In essence, he outlined the Wilsonian principle which, in the given situation, offered the only reassuring solution to the issue "we have a very simple but also the only tool of ascertaining the truth, the application of which we demand loudly so that we may see this issue clearly. And that instrument is the referendum. When we demand it,

WE INVOKE THE GREAT IDEA, SO BRILLIANTLY PUT INTO WORDS BY PRESIDENT WILSON, THAT NO GROUP OF HUMAN BEINGS, NO PART OF THE POPULATION OF ANY STATE, SHOULD BE PLACED AGAINST THEIR WILL OR WITHOUT BEING ASKED,

like a herd of cattle under the jurisdiction of a foreign state. In the name of this great idea, which is also an axiom of common sense and public morality, we demand a referendum in those parts of our country which they now want to tear away from us. I declare that we submit in advance to the result of the referendum, whatever it may be."

Apponyi thus formulated the Hungarian demand for a referendum, which paradoxically only succeeded in being enforced in Sopron and its environs, while it did not succeed in those areas where the Hungarians lived in a linguistic and ethnic majority.

Although it is debatable whether it was the right position to initiate a referendum for the entire territory to be annexed, or whether this demand should have been limited to the planned border areas, which were mostly inhabited by Hungarians, it is difficult to decide today. Pros and cons can be put forward for both alternatives, but the possible answer remains a fiction. Especially in view of the fact that the victors did not accept the Hungarian argument and did not make any substantive changes to the draft peace treaty. Yet a more just state of affairs could have been achieved at the moment of the birth of peace had the referendum been accepted and implemented.

At this point, a new element appeared in Apponyi's summary of the arguments: the question of minority rights. Apponyi raised his legitimate question in this way:

"MIGHT THE RIGHTS OF NATIONAL MINORITIES BE MORE EFFECTIVELY GUARANTEED IN THE NEW STATES THAN THEY HAD BEEN IN HUNGARY?"

The Count gave a twofold answer to his own question. On the one hand, he argued that Hungary's nationality policy was much better, indeed more advanced, than that expected of the new states. On the other hand, he argued that the Hungarian minorities in the new states had already suffered serious atrocities since the change of power, and that these were only likely to escalate in the future. Apponyi concluded his discussion on the protection of minorities with the following thought: "in the event of territorial changes being forced upon us, the protection of the rights of national minorities should be ensured more effectively and comprehensively than it is envisaged in the proposed peace plan submitted to us."

It was at this point in his speech that two further elements of his argumentation system appeared. On the one hand, an emphasis on the historical arguments, and on the other hand, an emphasis on the strategic-security policy factors, which are closely intertwined with them. The territory of Hungary, Apponyi emphasised, had played an important role in maintaining peace and security in Central Europe for centuries, as Hungary had protected Europe from the dangers of the East for ten centuries. The dismemberment of this principle and territory, which is well understandable from a security policy point of view, could lead to a high degree of vulnerability in the region, with unforeseeable consequences.

Towards the end of his speech, Apponyi presented his strongest set of arguments, the geo-economic reasons, the essence of which he summarised as follows: 'the historical Hungary thus has a natural geographical and economic unity that is unique in Europe.

NO NATURAL BORDERS CAN BE DRAWN ANYWHERE IN ITS TERRITORY, AND NONE OF ITS PARTS CAN BE TORN AWAY WITHOUT CAUSING THE OTHERS TO SUFFER.

This is the reason why history has preserved this unity for ten centuries." And what exactly he meant by this he explained in a few sentences earlier in his speech. He argued that if the edges of the country were annexed, the central part of the country would be permanently deprived of the raw material resources necessary for economic development, namely ores, salt, timber, oil, gas and labour resources. He again argued for the organic unity of historical Hungary, saying that the new state borders would split natural units, prevent the useful internal migration of labour and disrupt and abolish centuries-old economic traditions.

Moreover, Apponyi continued, the new states would also be hotbeds of irredentism, as their minorities would be of a higher cultural level than the majority nation. The emergence and presence of irredentism would not only endanger the new states, but would actually threaten them with disintegration. There is also a risk that these new states will not be able to effectively organise the economic life of areas inhabited by minorities with a higher cultural level, and thus integrate them into their own national economies. Thus, these territories will be left to languish and wither from an economic point of view. Economic decline and unemployment in particular, will inevitably lead to moral problems which will create the breeding ground for the advance of Bolshevism.

After the speech of Apponyi, [2] delivered alternately in French and English, and then summarized in Italian, Lloyd George, in response to a question from the presiding Clemenceau as to whether anyone wished to address Count Apponyi, asked for the floor, and said "Yes, I would like to ask a question." Lloyd George's specific question was: “Are there Hungarians living in ethnic territorial blocks beyond the new borders of Hungary?” [3] But what the British Prime Minister was actually interested in was the number of Hungarians who would live in neighbouring states if the designated borders were to come into force. He particularly wanted to know where the Hungarian population to be annexed would be located, i.e. directly along the border or further away, as a linguistic island.

Apponyi then, claiming that he could not hear well, took his chair and sat down at Lloyd George's desk, and laid before him an ethnographic map based on the 1910 census data, on which the Hungarian population was marked in red - hence the term red map (carte rouge) in Hungarian historiography - and which also showed the population density. On the map, Pál Teleki had carefully drawn the borders proposed by the Entente that very morning, so that Lloyd George could clearly see that the draft peace treaty would not primarily place remote linguistic islands under foreign rule, but Hungarian border areas. While Apponyi was explaining to Lloyd George, "who leaned over the map with interest", several other important politicians - Lord Curzon, Nitti - came to the table. Jenő Benda wrote: "Lord Curzon also drew nearer. Nitti got up from his seat and also leaned over the map. The secretaries were also grouped together prying from a reasonable distance. Macui, the diminutive Japanese, also approached, craning his neck to catch a glimpse, but Nitti's broad back blocked all view. Apponyi began to explain the map in detail. Clemenceau watched all this from his seat for a few minutes, then stood up himself and stepped up to Apponyi, who pointed out one after the other the great red spots trapped in Csallóköz, Ruszka-Krajna, Transylvania, in and around Arad, in Bácska: the bleeding wounds of the Hungarian nation."[4]

After this brief interlude with Lloyd George, no substantive issues were discussed. Clemenceau closed the meeting at 16.10. On 20 January, Apponyi and most members of the delegation travelled back to Budapest with the draft text of the Hungarian peace treaty to discuss it with the politicians at home and to decide on the next steps.

[1] The minutes of the January 16 meeting are published in several source publications, such as the Paper relating to the relations of United States 1919 the Paris Peace Conference. Volume I–XII Washington, 1942-1947. Volume IX, 872–884.; Documents on British Foreign Policy. 1919–1939. First Series. Volume I-VIII London, 1948-1958. Volume II 900–910.

[2] Jenő Benda, an eye and ear witness, reported: “And Apponyi now repeats in English what he has said so far, adapting it somewhat to the English way of thinking. And so it goes on: French and English passages alternate. Apponyi uses both languages with equal ease, clarity of pronunciation and eloquence. Although his original plan was to speak first in French and then in English, he now alternates between French and English every ten minutes, cutting the speech into small chunks. [...] Then he turns to Nitti and says a few more sentences in Italian. He knows that Nitti has understood his French, so he does not need to repeat what he has said so far. He just wants to remind the Italian representative that there was a time when the Hungarian and Italian arms fought not against each other, but side by side." Jenő Benda: The Peace... i. m. 61-62. The brief reflection in Italian by Apponyi was about not forgetting how many times the Hungarian and Italian nations had fought together on the battlefields, fighting side by side for freedom, even though they were confronted in this war. It was on this basis that Apponyi appealed to the goodwill of the Italians.

[3] Benda Jenő: A béke… i. m. 63.

[4] Ibid. 64.